The

China Forum

Shanghai, Suzhou, Hangzhou, China October 23 - 27, 2001

The

International Forum in China is about China and the Chinese. It is

designed for those who need to think strategically about China and its

role in the world. During the five days in Shanghai, Suzhou and Hangzhou,

the Forum will address the prospects for China’s integration with the

world economy, how China’s policies of reform, and the initiatives of

Chinese businesses and foreign investors are making this happen.

Participants are the senior executives of companies based in Europe, North

America and East Asia, and represent many countries of the world. They

meet in Shanghai, Suzhou and Hangzhou with those who have direct

experience in the marketplace in China and who work with foreign and

Chinese companies.

The

International Forum in China is about China and the Chinese. It is

designed for those who need to think strategically about China and its

role in the world. During the five days in Shanghai, Suzhou and Hangzhou,

the Forum will address the prospects for China’s integration with the

world economy, how China’s policies of reform, and the initiatives of

Chinese businesses and foreign investors are making this happen.

Participants are the senior executives of companies based in Europe, North

America and East Asia, and represent many countries of the world. They

meet in Shanghai, Suzhou and Hangzhou with those who have direct

experience in the marketplace in China and who work with foreign and

Chinese companies.

Reshaping China

If China were a train, we would admire its speed of travel and worry about control. China has continued to build momentum in its undertaking to reform its economy, and it has come a long way since Deng Xiaoping launched the efforts in the late 1970s.

Still, China is a country whose intrinsic caution, patience, and conservatism gave rise to such expressions as "The journey of a thousand li begins with a single step," and "we will cross the river by feeling the stones."

China is sprinting into its Olympic century, and much of the concrete reform and change currently unfolding could not be more radically different from the tradition of "feeling the stones." Just the infrastructure investment planned for the city of Beijing in preparation for 2008 is expected to top US$32 billion. In the next five years there are also plans to continue construction on the world’s largest dam, build the world’s longest high altitude railroad from Qinghai to Tibet, build one of the world’s fastest trains from Beijing to Shanghai, and continue investment in highways, water treatment, environmental recovery and protection projects, and power projects. There are plans to open domestic capital markets even more, continue the restructuring of government and major industry sectors, and continue China’s increasingly involvement with the global trading system.

China’s reform was launched with a series of dramatic regulatory changes. In China’s socialist market economy, the State continues to emphasize through policy and regulation major direct administrative control of major economic activities. In this scenario, with an active State Development and Planning Commission, an economically-focussed State Council, and a powerful State Economic and Trade Commission, regulatory reform is a major force of change.

But other forces are driving change in China. In addition to regulatory reform, the State-owned Enterprises themselves are facing up to commercial and market realities, and they are undertaking major changes. China’s imminent accession to the WTO has impacted the behaviour of foreign investors and domestic enterprises, and finally technology change is a force of major consequence in China’s evolving business environment. We will discuss these four change forces with an eye toward understanding their combined impact on China’s race forward.

Regulatory

Reform

Regulatory

Reform

Economic policy more than any other area has occupied the top Party and State officials. After the Tiananmen incident and several years of sluggish investment and transformation, Deng reignited both foreign investment and domestic reform during a trip to Shenzhen in 1992, when he signalled that Shenzhen’s fast growth pattern should be a model for all of China.

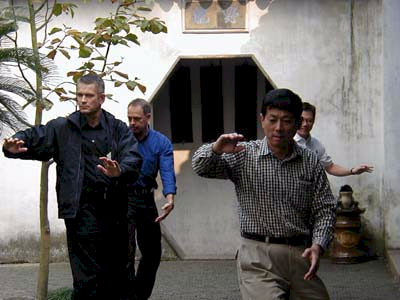

Participants experience the ancient martial art

of Tai Chi and learn about

the role it plays in

daily life for many people in Asia today.

Policy reforms continued steadily throughout the 1990s, and they included gradual reshaping of major sectors, like telecoms and iron and steel. But in 1998, as it became apparent China was approaching advanced stages of WTO negotiations, regulators addressed a series a problems. Ministries were merged or eliminated. New bureaus were created. The government was dramatically downsized, and the agenda to "separate regulation from business" was driven forward. Some sectors, like oil and gas, were consolidated into major companies, as China pledged to create its own Fortune 500 contenders. Other sectors, like telecommunications, saw incumbent monopolies broken apart, as China faced the need to introduce competitive mechanisms and forces to improve service and reduce prices. Severe liquidity problems in the banking sector were debated, and asset management companies were established to take over non-performing loans that had some prospect equity growth.

State-owned Enterprise Reform

State-owned enterprises continued to drain State coffers throughout the 1990s, and the problem remains the government’s biggest headache. At the macro level, the military was generally pushed out of ownership of large enterprises, and new share-holding models of ownership were permitted to convert the assets of enterprises and create an ownership stake for managers. SOEs began to explore equity markets, at home and abroad, and the emphasis began to shift away from joint ventures to other forms of capital and technology acquisition.

Some SOEs emerged as business winners, especially in consumer products, appliances, and electronics. Numerous trade advantages were extended to SOEs to encourage achievement of new market share and improved performance. Well-know names such as Hai’er, Kelong, and Huawei extended their market and investment reach overseas.

Spurred on largely by the requirements of oversea’s listings, some major SOEs made improvements in governance, financial controls, financial reporting, strategy development, organizations, management, and processes. They have pursued portfolio rationalization, more efficient deployment of capital, and brand development paths that were largely unknown among SOEs in the past. As the era of the joint venture came to a close, Chinese enterprises began to seek targeted, strategic partnerships, with both domestic and international firms.

Still, the SOE reform process remains unfinished in very significant ways. Mismanagement, corruption, misallocation, poor technology, and other legacies of the past are not easily overcome. SOEs as a whole are reported to be doing better, but direct contact with them indicates how difficult the road ahead is. For years, media coverage of the WTO process has focused on the coming of fierce competition, and the need to rise to it has occupied more conscientious SOE managers. For the stronger, they recognised an imperative to improve competitiveness across the board to continue their growth. For the weaker, it is a matter of survival.

WTO

Just as the first major joint ventures were being formed in China in the mid 1980s, China expressed interest in rejoining the GATT, and negotiation began. Some fifteen years later, the final agreements have been reached, and China is positioned to accede formally in the early part of 2002. Remaining hurdles are largely domestic, approval by Chinese authorities and legislative bodies, which is not expected to be troublesome.

The impact of WTO accession will be complex and significant, and it will be different for foreign investors and domestic companies. Long-time China observers agree that it will take a number of years, perhaps five to ten, for China’s regulations and administration of those regulations, at all levels of jurisdiction, to become compliant. There are major preserves within China’s economy where protectionism, bureaucratism, corruption, and expropriation are fundamental and deeply rooted. The negotiation process in recent years has been in the hands of the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation (MOFTEC), and there are many cases where the commitments are not understood outside or MOFTEC, even in ministries and bureaus that are directly impacted. The first challenge is to align the interests of many internal groups that have been opposed to the idea of China in the WTO, or opposed to specific provisions. The second is to educate them in the details of regulation and implementation. The third is to enforce the agreements at the local level as well as centrally. None of these is easy in the context of Chinese governance.

In

terms of horizontal, cross-sector agreements, China is committed to

greater transparency in the process of making laws, rules, and

regulations, and greater clarity, balance, and consistency in implementing

them. Intellectual property protection is to be enhanced, national

treatment is to be accorded all participants in the economy, quotas are to

be eliminated, and tariffs sharply reduced.

Visiting Suzhou Tefa Generatic Development Company

The large number of non-tariff barriers it to be reduced. Multi-tier pricing becomes illegal, and many unfair bidding and procurement practices have been identified by the working group, surfaced, and addressed. The WTO dispute process will create for the first time an external agency China has recognized with authority to address and adjudicate trade disputes. Some trade experts expect China’s entry to set the stage for an unprecedented number of dispute resolution cases.

Foreign investors are scheduled to get major access to service sectors and service activities related to their manufactured products. In financial services, insurance, banking, telecommunications, retail, distribution, logistics, information industries, and others are scheduled over time to open, at least to 50% foreign interests in joint ventures. Companies dealing in manufactured products gain significant rights to market, sell, distribute, and support their goods, overcoming the Byzantine system of regulations that in the past has plagued their efforts to get close to customers and develop direct understanding of the markets. In sales and distribution channels owned and controlled by foreign investors, domestically manufactured goods can be mixed with imported goods, and requirements to balance imports and exports, to import and transfer technology, or to invest in technology development on-shore are all to be eliminated.

For domestic investors, certain incentives given to foreign investors that domestics have long complained about will be eliminated. Future incentives used to guide economic activity will be based on industries and sectors, not the origin of investment capital or ownership. Tough competition will come to their doors, and for a period of time, the chronic overcapacity of China’s various manufacturing sectors will be further aggravated. Margins will be squeezed, and a degree of downsizing and rationalization will be unavoidable. Access to foreign markets will be improved and stabilized in some respects, but domestic manufacturers also assume new risks, in particular those related to special sanctions, anti-surge protection, and anti-dumping rules. Very few Chinese enterprises have any idea how to mount a defence against unfair trade allegations. Very few have the process control, documentation, and legal understanding to deal with these issues, and that will be a major risk to address in the next three years. With such actions increasingly used as trade and diplomatic tools, it is likely they will prove instruments dangerous to the economic well-being of Chinese enterprises and China’s export system if not addressed promptly and effectively.

Technology

The impact of technologies, especially information and communication technology on China is direct and profound. China is a country more characterized by its fragmented and regional dialects, jurisdictions, and economics than by the effective and uniform administrative reach of its central government, the unity of cultures and markets, or the consistency of any commercial practice. Among the frustrations of both foreign investors in China and aggressive and expansionist domestic firms, has been the difficulty of creating truly national markets and customer bases out of the fragmented pieces that exist on the map.

Now, the Internet and emerging eCommerce activities bring about the death of distance and ignore many traditional barriers to free internal trade. Even the spread of basic telecommunications services, and simple enhancements like toll free long distance dialing, have made it possible for call centers to service the entire country from a single location, and have begun to relax the grip of local interests and local protectors on local markets everywhere.

The Internet connects some 15 – 20 million Chinese to each other and to the outside world. Managing the impact of the Internet so it contributes in a way deemed "healthy" by the government is a serious matter that gets top-level attention in China. Generally, Chinese governments throughout history have had the interest and the means to centralize control of both the channels and content of information, be the medium bronze, silk, stone, or paper. Despite the commitment to manage everything from the content of on-line news carriers to the behaviour of chat room visitors, the government is struggling with an unprecedented array of information sources competing with their own. Although the vast majority of China’s citizens rely on State-run print and broadcast media for their knowledge of China and the world, the surfing population represents a key slice of urban students and young professionals that is growing rapidly.

In the recent tragic events in the US, as well as previous newsworthy events that the State media chose not to cover or cover lightly, vast numbers of Internet users turned to on-line information sites to follow their interests. Information previously not available, news, financial information, individual development opportunities, is now readily available. The Internet is credited with forcing China top leaders to recant various pronouncements and interpretations of events, like the recent tragic explosion in an elementary school, where the children were obliged to make fireworks. The Internet is reshaping markets, reshaping public discourse, reshaping the State-run media, and reshaping the relationship between the government and the people of China.

It is remarkable how much technology is a focus of China’s reformist leaders. Whether it is a solution to the acute water crisis in northern China, the anticipated pressure on the food supply, the general environmental degradation, or management of the Internet, the leadership appears to have faith that technology solutions are to be found. China’s strongest schools and strongest students still are in technology related fields. Its top leaders overwhelmingly come from engineering and science backgrounds. In its long-term economic plans, China is committed to growing away from an economy based primarily on the export of cheap labour. As the recent diplomatic spats over allegations of technology theft indicate, China is both proud and sensitive about its ability to develop technology that is at world class levels and capable of making China a world-class competitor in technology sectors. In the years to come, we will see many of China’s leading companies struggle to establish a position in global technology markets.

Conclusion

The next five years are likely to see dramatic changes in China, not only the economy but the entire political body. In late 2002 new leaders will emerge from the 16th Party Congress. Such succession watersheds, which are not guided by well-defined and transparent rules and procedures, are always times of risk. The changes will happen against a backdrop of increased potential for social turbulence, turbulence driven by separatist activities in Xinjiang and Tibet, and driven by economic inequality between the eastern seaboard and the inner provinces.

How these forces of change will transform China is difficult to predict. Economic reform on the scale and at the pace we are witnessing is unprecedented. It inevitably entrains many forces for social and political change. But the commitment of the Party and its leaders to maintaining monopoly control, against an array of new challenges and pressures, is also not to be underestimated.

|

Will SOE restructuring slow in the face of a global economic slowdown? If so, what are the implications? | |

|

How will WTO implementation impact foreign companies? How will it impact domestic firms? Who will be the winners and losers? |

|

If the transition to a WTO environment is too painful (e.g. rising unemployment, political dissent, etc.) over the next few years, what action might China take? | |

|

Will the Internet lead to more pluralism within China? Is it already a catalyst for increased transparency and openness? How is the Internet changing information flows in China? How is the government managing this? |

More Information: